Entry 6 Day 35 05 November Altitude: 121 ft Distance: 15,409 km Speed: 0 knots/hr

Meet our station on skis

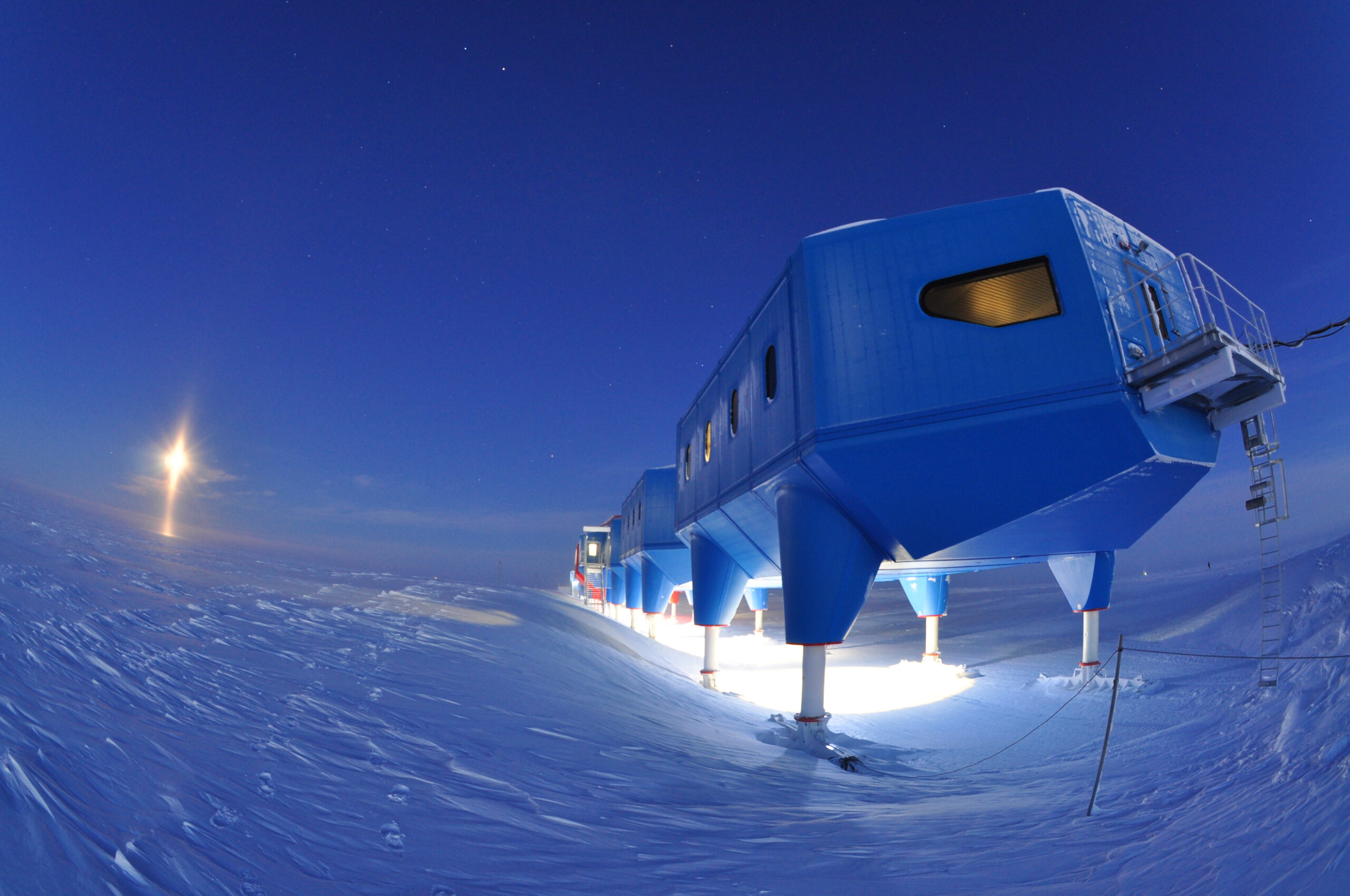

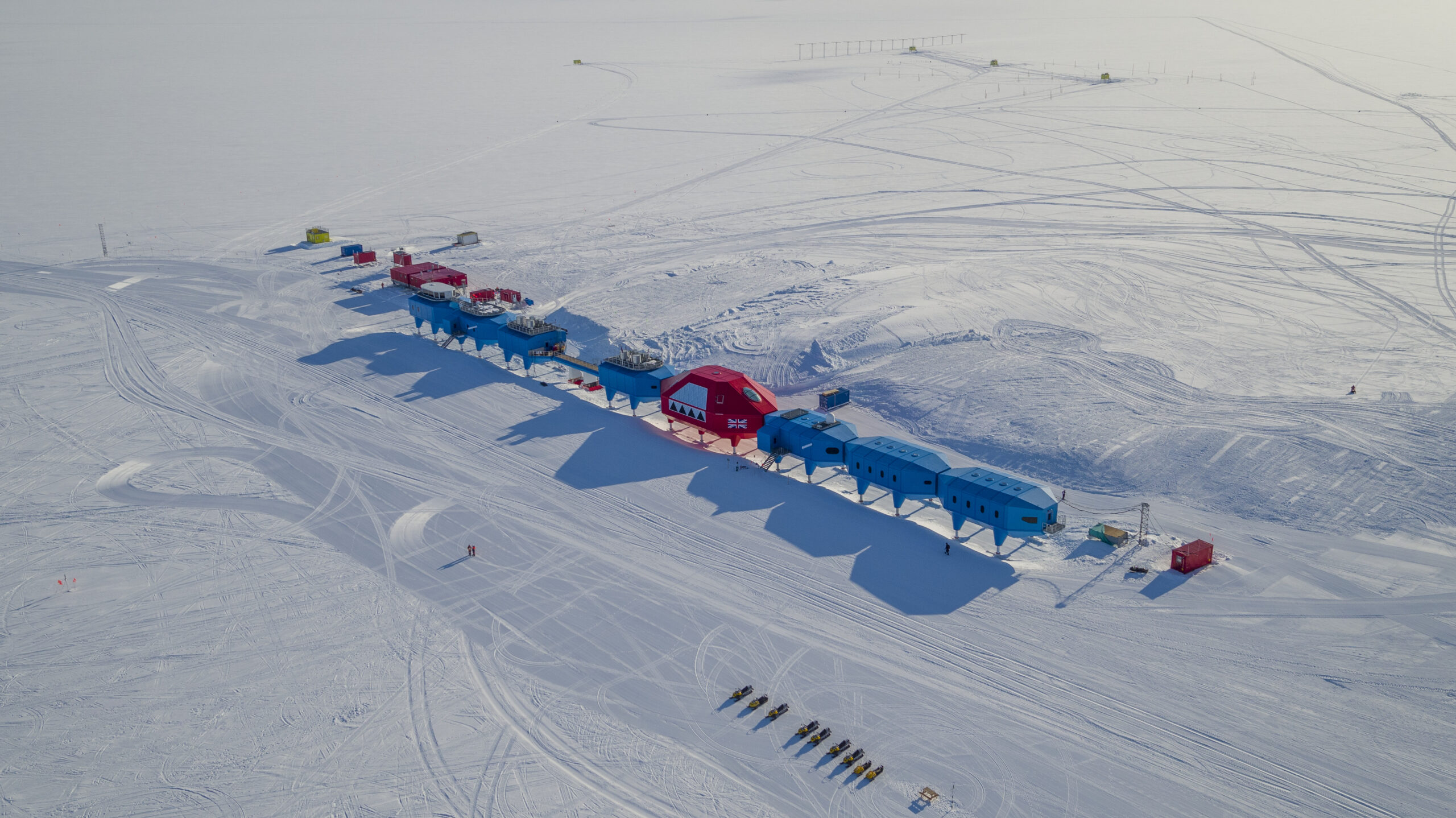

This week, we’re introducing our famous station on skis. Halley VI Research Station looks a bit like a space station – pods of bright blue and red, surrounded by a vast, icy landscape.

On a sunny, summer day, the temperature is typically around -10°C. But in the depths of winter, it can get as cold as -55°C! When it’s very windy, snow is blown around, making it hard to see beyond a few metres. People say it’s like being inside a ping-pong ball, where the view is just white in all directions.

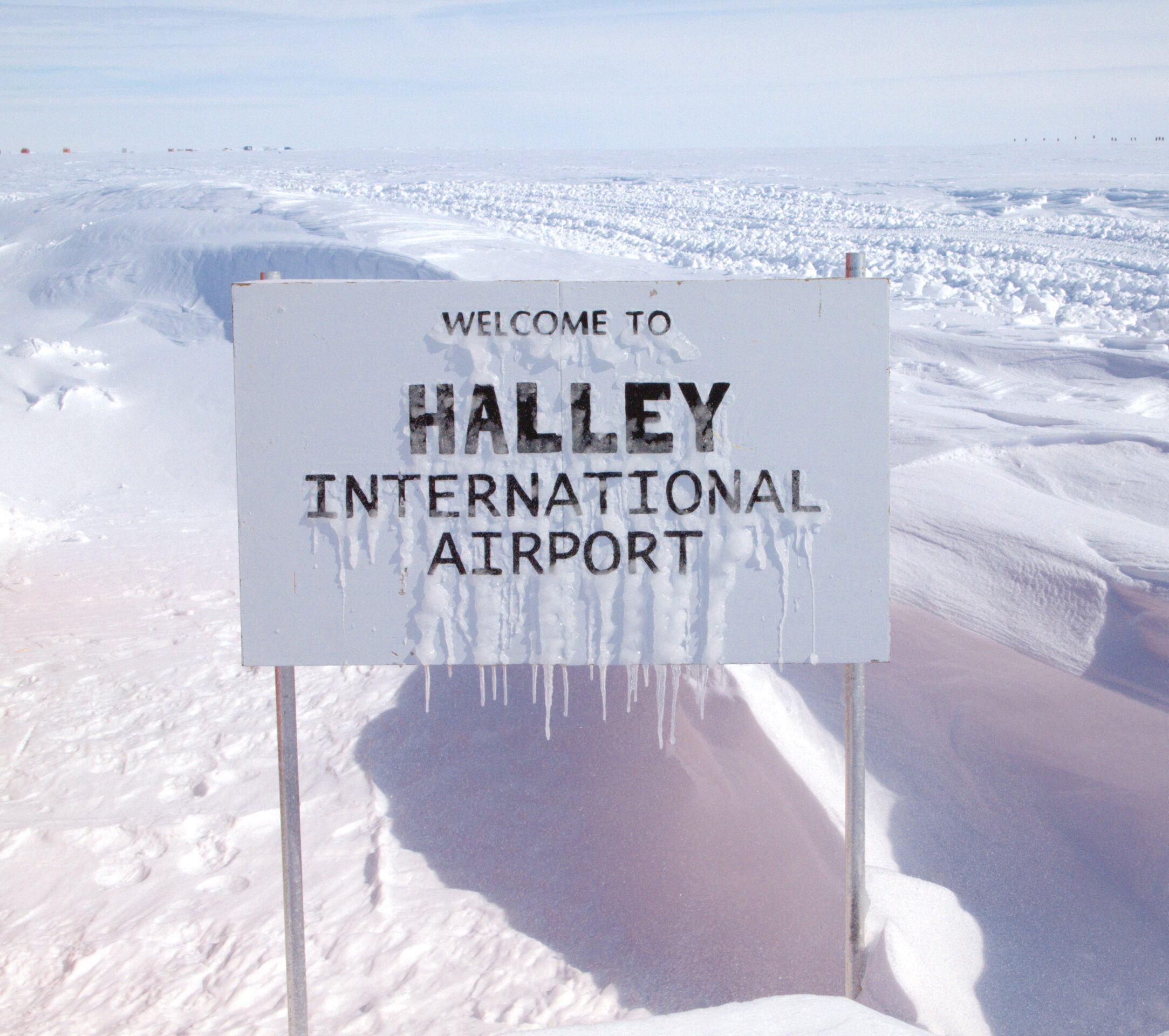

Planes land on a snow runway at Halley

Constantino Listowski

Constantino Listowski  Constantino Listowski

Constantino Listowski In bad weather, you can only see a few metres

Dan McKenzie is the Station Leader at Halley VI. Over the past week, he’s been making the long journey from the UK to our most remote research station.

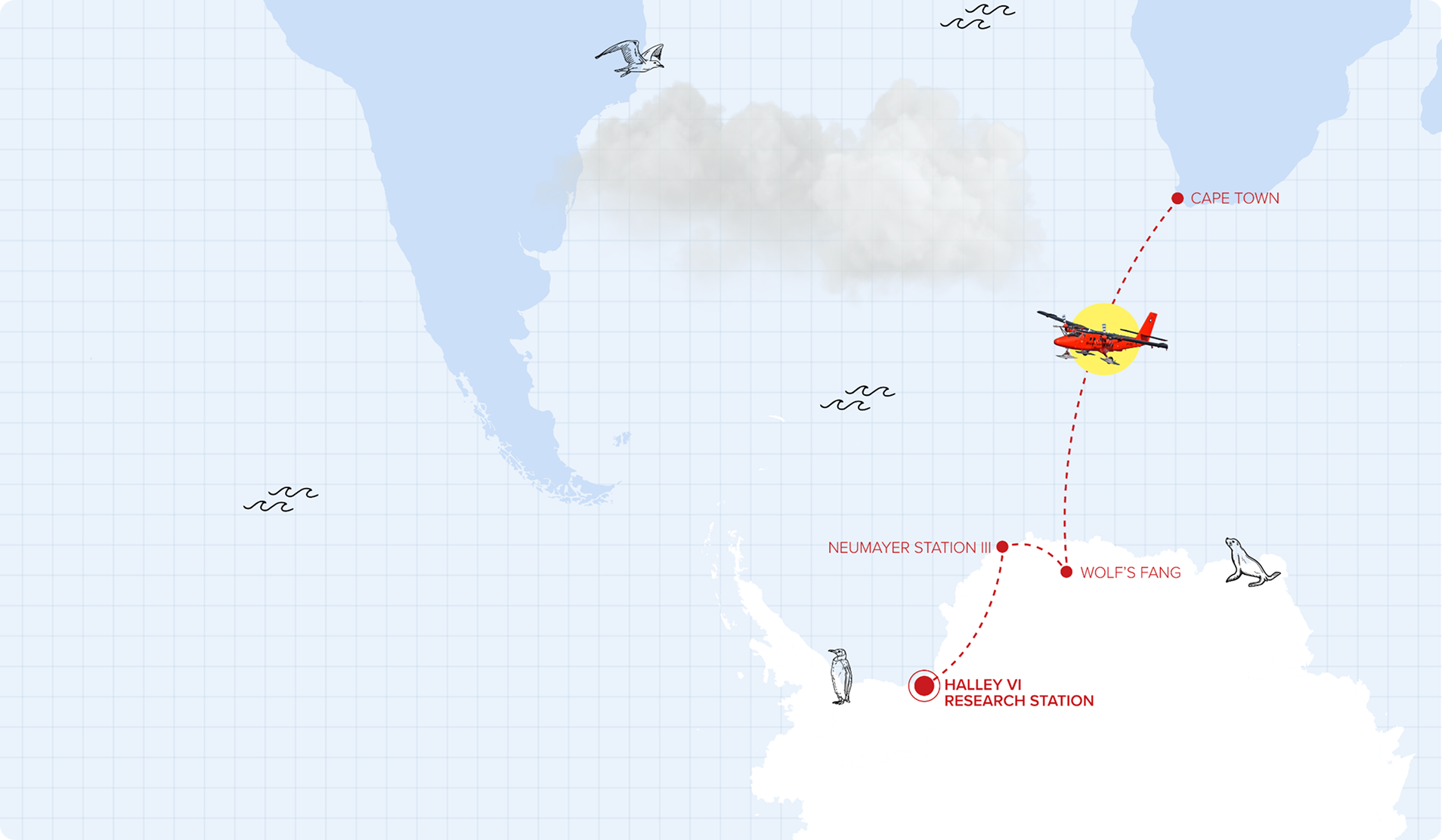

To get to Halley, the team fly from Heathrow Airport, in the UK, to Cape Town in South Africa. From there, they fly to a place called Wolf’s Fang – a camp on the Antarctic continent.

This is where Dan and the team are now. They’re waiting for a window of good weather so they can fly on a Twin Otter to Halley, via Neumayer Research Station, run by the German Antarctic Programme.

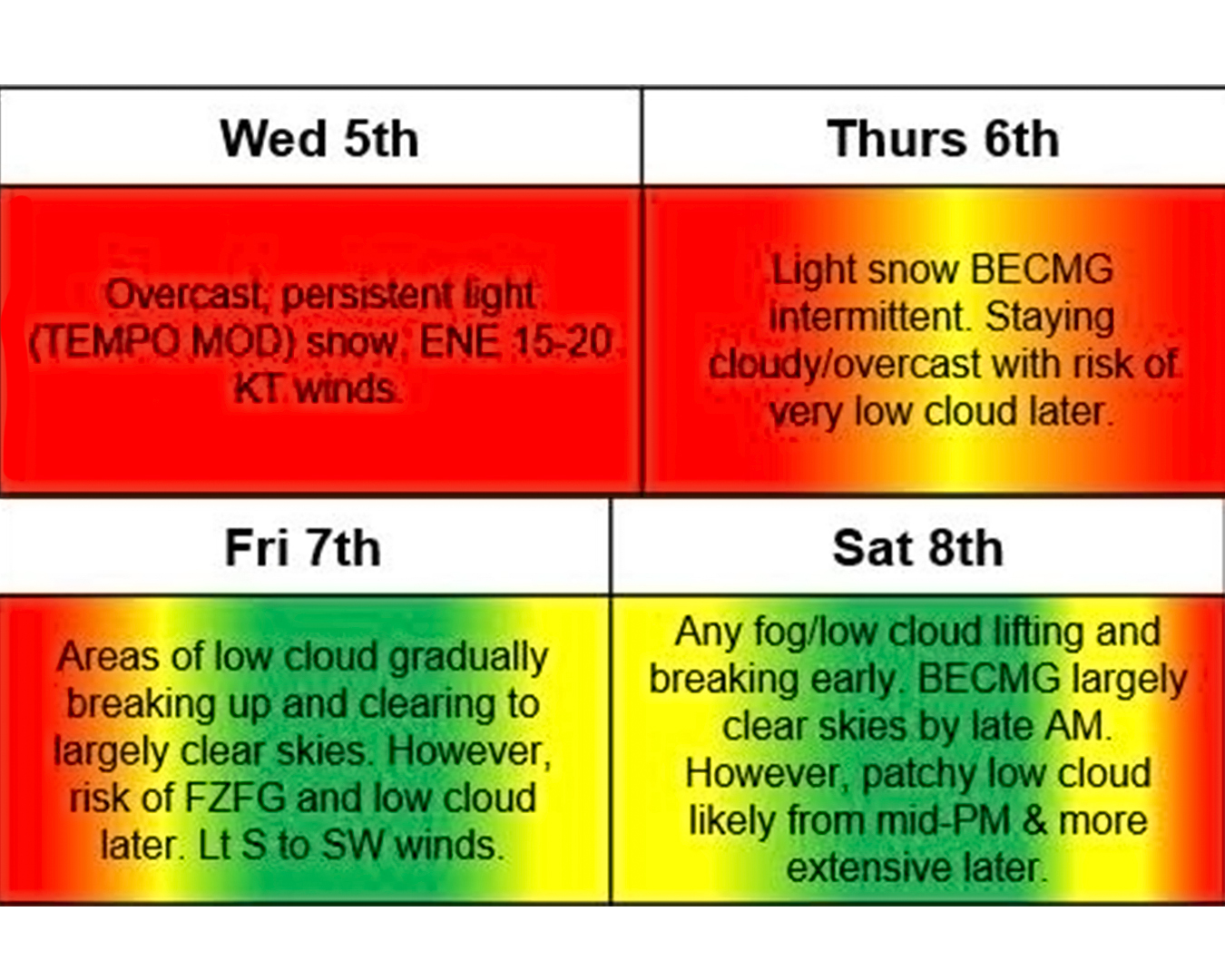

Dan and the team were meant to arrive at Halley today – but Antarctica is unpredictable, and we always plan for weather delays.

Here’s the summary weather forecast at the moment – that’s a lot of red!

It was put together specially for these flights by the UK Met Office forecaster based at Rothera Research Station. However, it’s a huge and remote area, which makes the forecaster’s job very tricky.

Check out these photos that Dan sent you from the remote Wolf’s Fang camp.

What I think makes Halley special is the people. It’s in a beautiful, harsh and sometimes ethereal environment that you can’t quite imagine until you see it, but the real beauty of the place is the people and the community around you. That’s what keeps people coming back.

Dan McKenzie, Halley Station Leader

Arrival at Halley

Because Halley VI Research Station is on an ice shelf, there’s no permanent runway. Instead, there’s a snow runway which means planes have to land on skis!

Constantino Listowski

Constantino Listowski  Martin Bell

Martin Bell Once they arrive in Antarctica, our Twin Otter aircraft are equipped with skis – which sit over the wheels and can be deployed by the pilot.

Here they are getting fitted up.

Where is Halley VI?

Halley VI is the world’s first relocatable research station. It it has giant skis – and that means it can be towed across the ice.

Why is this important? Well, Halley VI sits on the 130-metre-thick Brunt Ice Shelf. An ice shelf is a floating body of ice that sits on the ocean. This ice shelf flows slowly out onto the Weddell Sea, where chunks eventually calve off as icebergs.

This means, over decades, Halley VI will move closer and closer to the sea. So, we need to be able to move the station inland to a safe and stable location.

There are also giant cracks (or chasms) the develop in the ice shelf, that will eventually split off a giant iceberg! In a few weeks, we’ll introduce a team who want to be able to predict how these massive cracks develop.

In 2015, we decided to use Halley Research Station’s special ability to relocate. This was because a big chasm started growing across the ice shelf.

We moved it to the other side of the chasm, to keep it safe and sound on the stable part of the Brunt Ice Shelf.

In 2023, the crack made it all the way across the ice shelf and made an enormous iceberg, which was the size of Greater London.

This moment is what we prepared for when we moved Halley VI.

The other cool thing about Halley is that it has hydraulic legs, so the station can be raised to keep it from being buried by snow.

A huge job for the team every year is individually raising each leg, packing it out with snow, lifting the whole module up to its new height, and then levelling out the ground. Digging is a very big part of Antarctic life!

Martin Bell

Martin Bell

Martin Bell

Martin Bell Studying the skies and space

Halley VI is in a really special location for studying the skies and atmosphere. It sits in something called the auroral oval, making it the perfect place to study space weather – and to watch the Aurora Australis (or the Southern Lights).

This impressive light display in the sky happens when charged particles from the Sun interact with atoms in the upper atmosphere, creating streams of red and green light.

A bolt of Aurora Australis

Because of its prime location for space weather, data from Halley is used to create weather forecasts for space. This helps to protect satellites from space storms. These satellites are vital to our lives – they help us navigate, predict and monitor natural disasters and provide our internet.

Can you imagine skiing to work? That’s what some people at Halley have to do. Because the research station is so remote, scientists can take measurements of very pure air, snow and atmosphere.

About 1km away from the main research station is the Clean Air Sector laboratory, where this data is collected. To protect the lab from contamination, vehicles are not allowed nearby, so the team have to walk or ski to get there. The data collected gives scientists around the world long-term data about the state of the air and atmosphere.

Antarctic research station or space station?

Sounds of space

What does space sound like? Using a special instrument called Very Low Frequency receiver, scientists can record radio waves made by our planet. These waves can be used to understand space weather, but it can also be converted into sounds we can listen to!

Spherics

These are caused by lightening storms. Most of the spherics we detect at Halley come from lightening over the Amazon Rainforest in South America, and the Congo Basin in Africa, both more than 8,000km away.

Whistlers

These also occur mostly from lightning and travel along the Earth’s magnetic field lines.

Chorus

These noises, created during an aurora, sound a little bit like birdsong.

Want to hear more?

Listen to this Sounds of Space album – music that uses some of the sounds you’ve just heard! It was created by Dr Nigel Meredith (a space weather scientist at British Antarctic Survey) with composer Professor Kim Cunio and artist-engineer Diana Scarborough.

Discovering the ozone hole

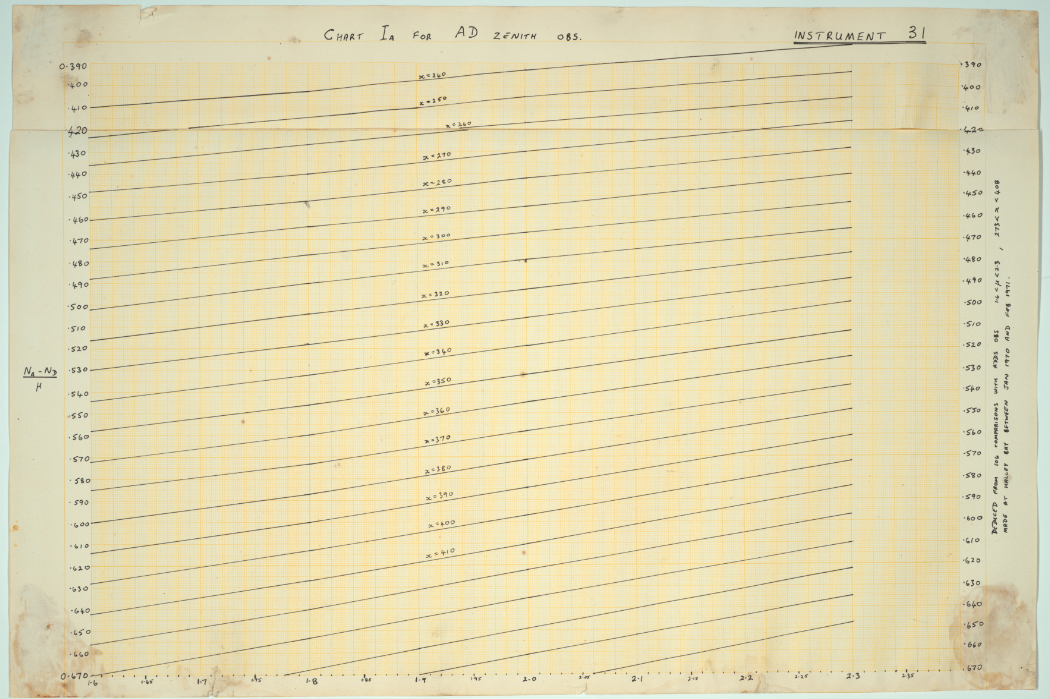

Ozone measurements have been made at Halley since 1956. It was this long-term data set that helped scientists spot something had changed and led to the discovery of the ozone hole in 1985.

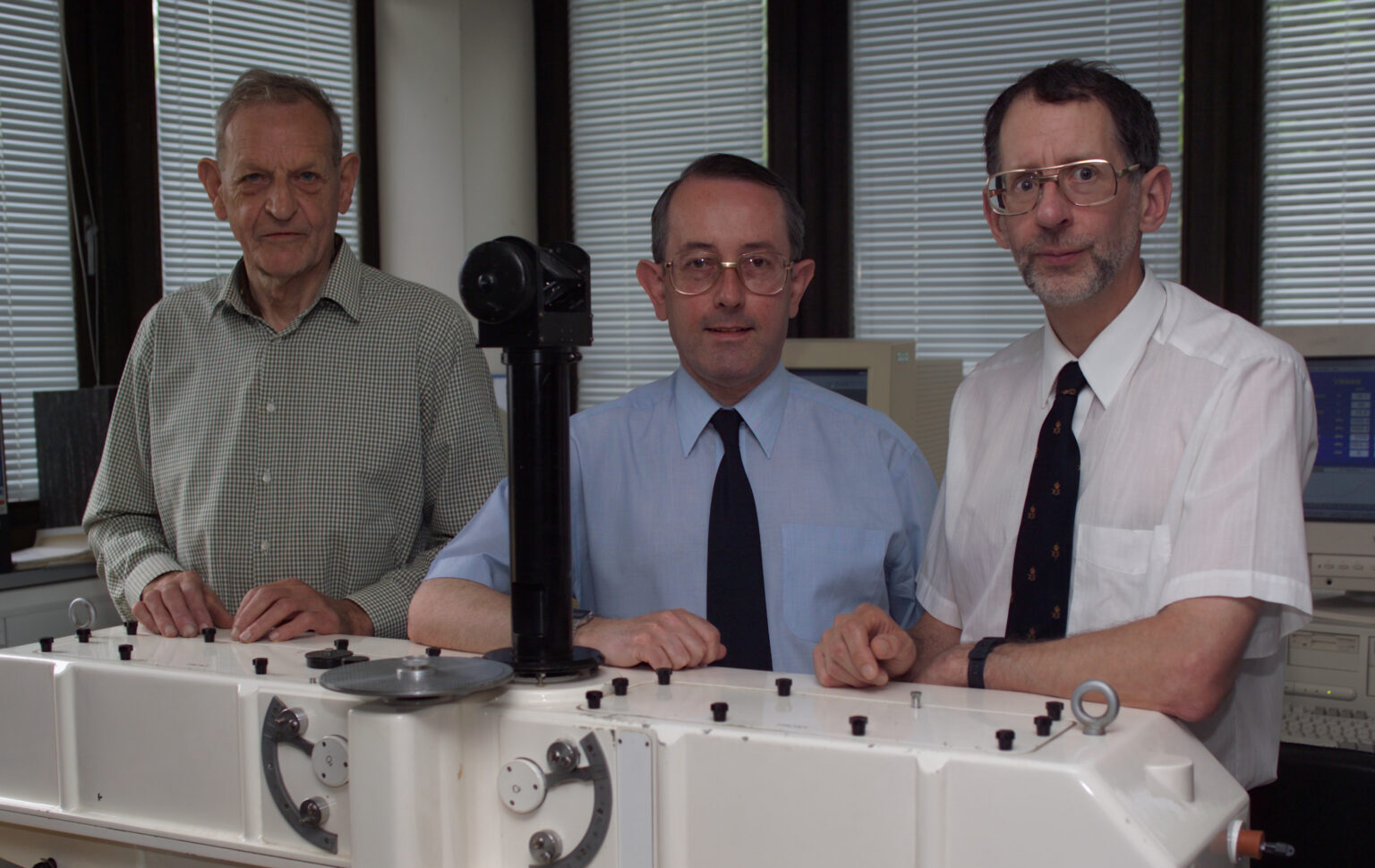

This year, we celebrated 40 years since the ozone hole was discovered by three BAS researchers – Joe Farman, Brian Gardiner and Jon Shanklin.

The three scientists who discovered the ozone hole with the Dobson Spectrophotometer, which still measures ozone at Halley today

When we first noticed the change in numbers, I remember thinking it might have been something peculiar to Antarctica. We checked and rechecked the data, working through the backlog of observations. But eventually we realised we were seeing something significant – and potentially alarming.

Jon Shanklin

The graph that showed something had changed

This discovery led to an international agreement (called the Montreal Protocol) that froze the creation and use of CFCs – the particles causing the hole in the ozone layer. These particles mostly came from aerosol cans and fridges. Today, the protocol stands as one of the most successful international agreements ever implemented.

Meet Antarctic architect Hugh Broughton

Hugh Broughton has designed two of British Antarctic Survey’s polar research stations – Halley VI and our brand-new Discovery Building at Rothera Research Station. So how do you design a building in Antarctica? We quizzed Hugh to find out…

Hugh Broughton Architects

Hugh Broughton Architects  Karl Tuplin

Karl Tuplin What’s the biggest challenge when designing a building for Antarctica?

Building in Antarctica is much harder because of the extreme weather. The temperatures are very cold, there are strong winds and lots of snow. Getting materials to Antarctica is also difficult and expensive – we have to think very carefully about everything we need.

How do you make sure the building doesn’t blow away in Antarctic storms?

First, we design the building with rounded corners and sloping surfaces to make sure the strong winds flow around the building. Then we place the building in the right orientation to reduce the effect of the wind.

What materials can survive temperatures of -40ºC without breaking?

For the building’s cladding we use insulated panels, faced with fibreglass or metal. These panels have a warm middle layer. Our favourite material – used at Halley VI – is fibreglass which is very strong, light and doesn’t rust. It’s also easy to mould into very complex geometries, so we can build any shape we want! We also use a special kind of steel that can resist very low temperatures.

How do you get a massive building to Antarctica when there are no roads?

Buildings are usually prefabricated in small components which are then packed into shipping containers. These containers are then sent to Antarctica on big icebreaker ships which can cut a route through the ice surrounding the continent. Once they reach Antarctica, the containers are loaded onto special trailers and towed to site by bulldozers. Once they’re at the right location, the small components are put together – a bit like a giant LEGO set – to build the new station.

Pete Bucktrout

Pete Bucktrout  Anthony Dubber

Anthony Dubber How do you know the design will work?

We do lots of tests! During the design phase we can do wind tunnel tests and snow modelling tests on small-scale models of the design. This helps us understand how the building will behave once its built.

What’s the cleverest design feature you’re most proud of?

There are so many clever design features – special joints to make sure heat can’t escape, for example – but we’re very proud that Halley VI is the first fully relocatable building ever built in Antarctica. It can be raised or lowered on hydraulic legs and can be moved to another location on the ice shelf when required. This is pretty special for a building in the most inhospitable environment on the planet.