Entry 10 Day 63 03 December Altitude: 0 ft Distance: 13,738 km Speed: 0 knots/hr

Science from the sky

As we enter December, we’re heading towards midwinter here in the UK – the shortest day of the year. But due to the tilt of the Earth, in Antarctica, summer is on the way!

With the better weather in Antarctica, comes a very intense period of science.

It’s science season in Antarctica

This week we cast our eyes upward and learn about all the different ways we study Antarctica from above. From drones and planes to satellites all the way up in space – there’s a lot we can learn about the frozen continent from the skies.

Science on a plane

Do you remember we have a fleet of four Twin Otter planes? As well as transporting people and equipment, they can be kitted out with a range of science instruments that take measurements and collect data about the surrounding environment.

Four Twin Otters support our polar science from the sky

- Aerial photography: through the hull of the Twin Otters, we can attach an aerial camera which points down to the ground. With it, we can take photographs from 3000ft!

- Airborne geophysics: we can put instruments in the Twin Otter to monitor the physics of the Earth – think gravity and magnetism (the force of attraction between different objects). We can even use radars to see under and measure the ice.

- Airborne meteorology: different sensors collect data on temperature, the water vapour and turbulence (the unsteady movement of air). We can also look at more complex processes like heat flux – which, in simple terms, is the transfer of thermal energy from the Earth’s surface to the atmosphere.

- Remote sensing: our planes can be fitted with something called a hyper spectral imaging spectrometer – a complex piece of kit that can look at different kinds of light reflected and emitted from a surface.

One example of this science in action is when we mapped the ground underneath the giant Thwaites Glacier to help us learn more about how it moves.

Watch the video – opens in new tab

Carl Robinson is the Head of Airborne Survey Technology at BAS – he develops and leads exciting science missions on board our planes. He’s in Antarctica at the moment and shared these clips from a project he’s working on to look at how much snow has accumulated on the Larsen Ice Shelf, on the east coast of the Antarctic Peninsula.

Vicky Auld

Vicky Auld

Vicky Auld

Vicky Auld Science from space

Satellites are objects that orbit around a planet, moon or star. They can be either natural or artificial. For example, the Moon is a natural satellite because it orbits Earth. Artificial satellites are made by humans and have lots of different jobs to do!

Scientists at British Antarctic Survey use these satellites to take pictures of Antarctica to see what’s going on down there. One really important job is counting Antarctic animals to see if their numbers are going up or down.

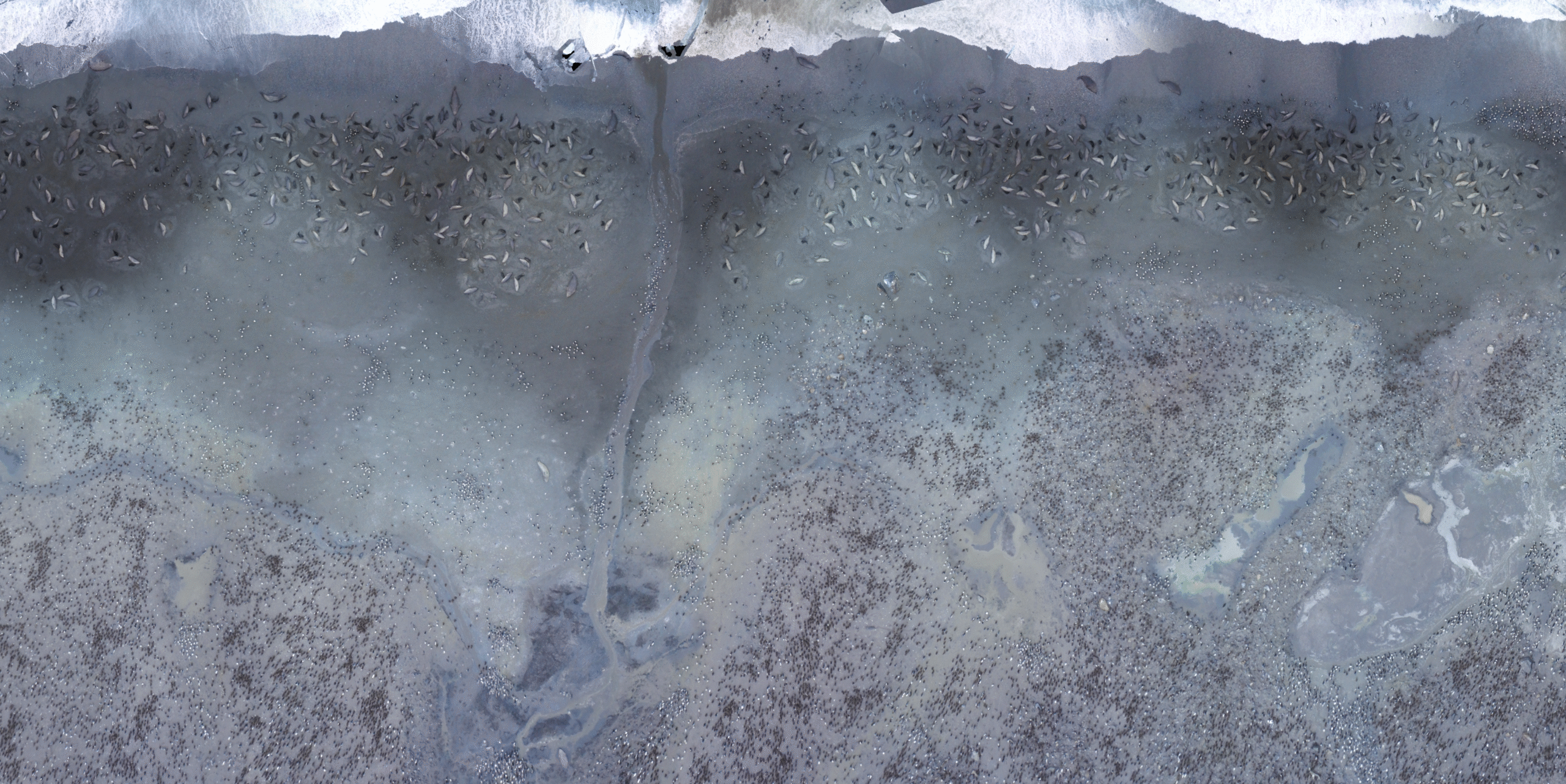

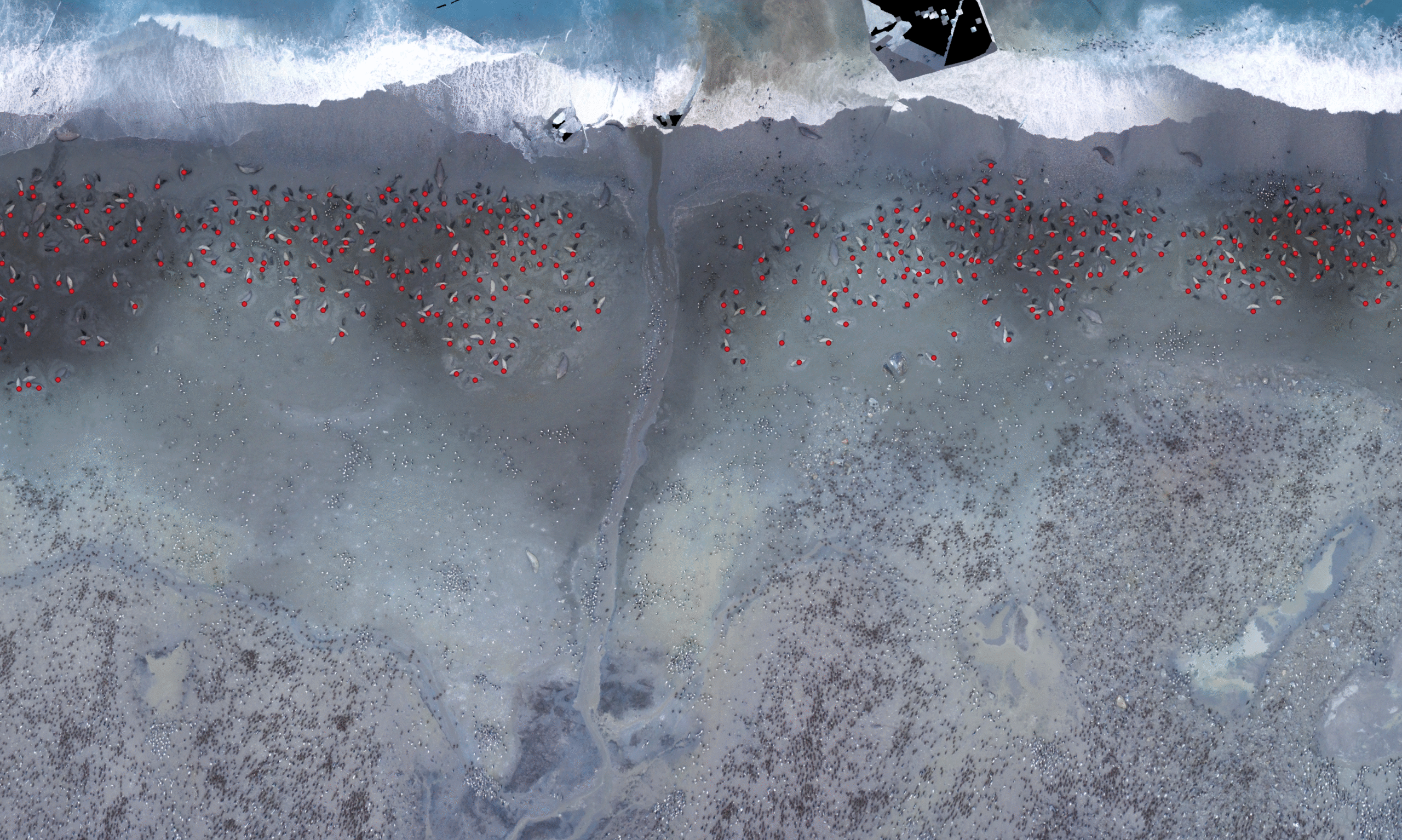

A satellite image of southern elephant seals…

The old way: Walking and counting

Satellites are relatively new technology, so how did people count animals before? Well, scientists had to walk among the animals and count them one by one.

Not only is this time-consuming, it’s difficult for other reasons. Take seals, for example. Seals are very friendly creatures who love to cuddle up together in big groups. When seals pile on top of each other, it’s really hard to tell where one seal ends and another begins, and as brave as our scientists are, they’re not going to break up a bunch of seals having a cosy snooze!

The new way: Satellites and drones

Luckily, satellites make counting much easier. They give us a bird’s-eye view from space, so we can see all the animals at once.

… and a drone image

Phew! Let’s all breathe a sigh of relief for our scientists’ poor feet.

But hang on a sec… looks like the scientists are still needed on the ground after all! Because the pictures are taken from so far away, it can be tricky to spot the animals. So, someone has to check whether we can accurately count how many animals are in the pictures taken by the satellites.

Southern elephant seals and king penguins in St. Andrew’s Beach, South Georgia.

A recent study used two different methods to make sure the satellite images could be used to accurately count elephant seals. They counted the seals from the ground and then using drones. Drones are particularly useful for telling seals apart when they’re snuggled together!

Connor Bamford

Connor Bamford

When all three methods agreed, scientists knew they could trust the satellite pictures.

This means that when our scientists aren’t in Antarctica over winter to manually count the seals or send up the drones, they can rely on satellites to continue counting the seals for them and help build long-term population records.

Check out this video to learn more about how we use new technology to count animals.

Extreme weather in extreme places

We’ve all seen more extreme weather where we live, and around the world. Maybe it’s intense flooding, more frequent tornadoes, or record-breaking heatwaves in the summer.

The increase in extreme weather events is the erratic, sharp end of climate change. But what happens when extreme weather hits the continent of extremes – Antarctica?

We talk about Antarctica as an extreme place – but for the plants, animals and delicately balanced systems there, those generally cold, windy and snowy conditions are completely normal.

And while extreme weather events might only be temporary, they can have a dramatic physical impact.

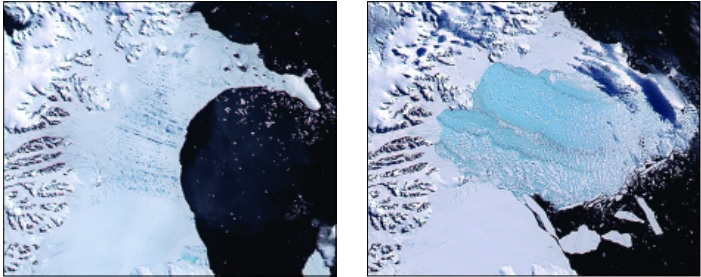

All the way back in 2002, part of the Antarctic Peninsula experienced an extremely warm summer. This caused lots of melting on the surface of the Larsen B Ice Shelf, which scientists think contributed to the dramatic break-up of the ice shelf over just a few days.

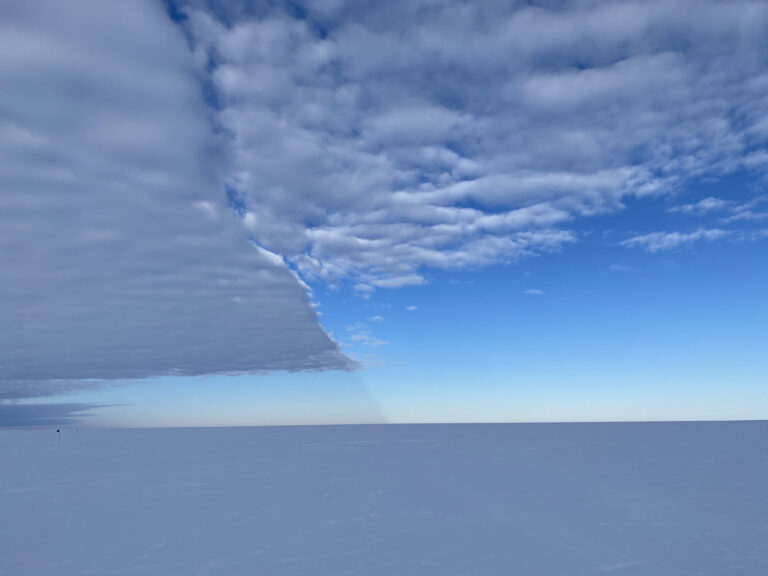

A decade later, in March 2022, on the high, cold plateaus of East Antarctica, the most extreme heatwave recorded anywhere in the world saw temperatures to rise by 38.5°C above the local average.

It was caused by a long, narrow band of warm and moist air from the tropics moving unusually far towards the poles, bringing extreme precipitation and relative warmth all the way to Antarctica. This phenomenon is known as an atmospheric river.

Warmer air can hold more moisture, which leads to a general increase in extreme precipitation, or rainfall.

The extra moisture led to more precipitation over the Antarctic, most of which fell as snow. Counterintuitively, this meant that the heatwave actually added to the overall mass of the sheet. Complicated stuff!

Extreme weather in Antarctica can take the shape of snowfall

Antarctica’s weather may seem very far removed from our daily lives, but what happens there affects all of us.

Antarctica’s vast ice sheets are part of Earth’s delicate balance of climate, and factors that upset this balance have knock-on impacts everywhere. From sea level rise to the extinction of charismatic animals like emperor penguins, extreme weather is likely to have extreme impacts.

Speaking of drones…

Check out this amazing drone footage taken while the ship was at Signy Research Station last week.

Signy Island is one of the South Orkney Islands, and the station was closed through the harsh Antarctic winter winter. The RRS Sir David Attenborough sailed as close as possible to the island, before the station team were dropped off for the summer in our smaller work boat, Terror.