Entry 7 Day 42 12 November Altitude: 1,435 m Distance: 7,741 NM Speed: 0 knots/hr

Welcome to Sky-Blu field camp

This week we’re heading into the deep field, to our remote Sky-Blu camp. The runway is made of hard blue ice. This means aircraft have to land on wheels (not their skis), and it takes a lot of skill from the pilots to stay in control on such a slippery surface!

But first, let’s catch up with Dan (Halley’s Station Leader) and his epic journey to reach our station on skis. And don’t miss his photos and videos from the trip so far… including some VERY cute emperor penguin chicks and a musical send off!

It’s always a challenge getting a good window of weather to fly into Halley VI, and this year is no different. On Thursday, we set off from Wolf’s Fang in blue skies to our next stop – the German research station Neumeyer.

Neumeyer has been a really interesting experience, seeing how another nation does polar science and to experience the wonderful German and polar hospitality. We visited a local emperor penguin colony and got a musical send off as we set off for our next stop. However, we ended up turning around due to bad weather. On Tuesday we tried again and made it as far as the Norwegian Troll research station.

Thanks to the wonderful team at Neumeyer for their kindness and welcoming spirit!

Dan McKenzie

Dan McKenzie

Dan McKenzie

Dan McKenzie Welcome to Sky Blu

Sky-Blu is one of our logistics hubs on the Antarctic continent. It’s a vital stop to get scientists out into the depths of Antarctica, to study things like the ice sheet and climate.

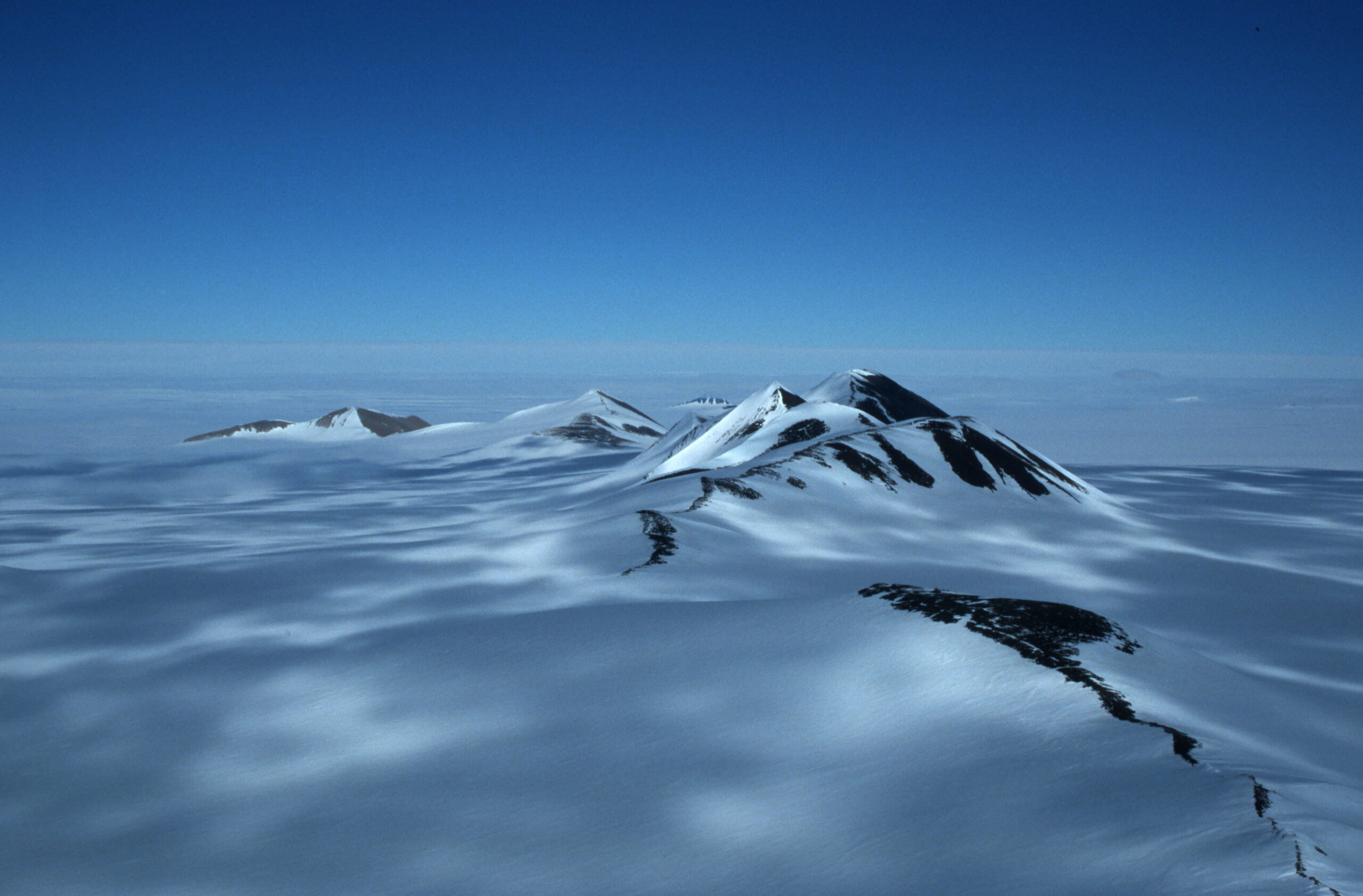

It’s about 800km south of Rothera, near the Sky-Hi Nunataks. Nunataks are peaks of mountains, poking above the surface of snow or ice.

The camp was officially opened last week after the winter season. Some of our intrepid team made the almost four-hour flight from Rothera and they have been busy uncovering everything after the winter and pitching tents ready for the science season to begin in earnest.

Sky-Blu camp

Life at Sky-Blu is pretty basic – it’s basically a polar campsite. There’s a bright red melon hut (an insulated bubble-like building where the team eat, plan activities and chat) and pyramid tents for people to sleep in.

Sky-Blu is an important place for our Twin Otter aircraft to stop and refuel, and for the pilots to have a well-earned break. This means time at Sky Blu can be pretty quiet, interspersed with bursts of activity when planes come in and regular weather observations that are used to brief the pilots flying in from other places.

A lot of time is spent clearing the blue ice runway! This runway is even big enough for our Dash 7 to land there to drop off people and cargo.

From Sky-Blu, field teams will be taken onwards into the field to do their science projects.

Life at Sky-Blu

Explore Sky Blu

Want to see Sky-Blu for yourself? Explore with this virtual tour. Keep your eyes peeled – we’ll be sending you on a treasure hunt around the camp next week!

Explore Sky Blu

Extreme camping

Camping in Antarctica isn’t just camping – it’s extreme camping. With temperatures of around -20ºC, polar campers need to be very prepared.

A team is currently busy setting up a field camp in Palmer Land, a flight away from Sky-Blu. They’re getting ready for researchers and engineers to spend the next four months drilling ice cores as part of a project called REWIND. We’ll find out more about what they’re up to next week.

Pilot Vicky dropped more of the team off, and she sent us this video of them setting up camp and making a well deserved cup of tea!

So what on earth do you pack for a camping trip in Antarctica?

What people wear in the Antarctic has changed a lot since the first explorers visited the frozen continent. We know a lot more about how our bodies work in the cold, and the properties of different materials. Our researchers need to feel warm – but look cool!

Matthew Cridland, who decides what researchers pack in their kit bags before heading to Antarctica, says:

Layering is the secret to keeping warm in Antarctica. Lots of layers of thin clothes is much better than one or two layers of thick heavy clothes. Layering traps air between each item – and this is what keeps you warm!”

Even though it’s cold, you can get pretty sweaty when you’re wrapped up and hiking to do some research, or lugging heavy science equipment around. All the layers of clothing help to ‘wick’ the sweat away from the skin. This is important because if your clothes stay damp, it will make you very cold.

Even though it’s cold, you can get pretty sweaty when you’re wrapped up and hiking to do some research, or lugging heavy science equipment around. All the layers of clothing help to ‘wick’ the sweat away from the skin. This is important because if your clothes stay damp, it will make you very cold.

Want to learn more?

Check out this ‘What (not) to wear’ game from the Discovering Antarctica website.

Did you know?

We donate Antarctic cold weather gear to a local homelessness charity in Cambridge?

Food – glorious food

There are no chefs in the deep field so the Field Guide tends to do most of the cooking – although everyone mucks in.

Most food is dehydrated, so as long as you can boil water, you can make some pretty tasty meals! Think things like chilli, vegetable curry and mac’n’cheese. The food has lots of calories in to sustain everyone working hard in the field.

The boiling water comes from melting snow. But… it’s not as simple as you might think. There’s a real knack to it, and if you add snow straight to a hot pan, it just burns off and disappears.

First, you need to start with a little bit of water and heat that up. Then you add a small amount of snow, which absorbs the warm water and starts to melt. When the snow has disappeared, you add more snow. It’s a time-consuming job!

At larger camps, where there is a little bit of electrical power (like Sky-Blu) teams can have a bread-maker. There aren’t really any natural smells in Antarctica, so the smell of fresh bread in the morning is a real luxury.

‘Lying up’ and waiting for a weather window is a big part of field camp life!

And what about… toilets?

The set up for toilets can look very different depending on where you are. For people that are staying in a field tent, a common field toilet setup is a bucket dug into the snow with a wooden seat on top. Normally, this is in a separate tent, or sometimes in an igloo (called a ‘pooloo’!)

All solid waste is collected and taken back to the nearest research station where it’s disposed of.

Deep-field toilets can be a bit chilly!

Peter Convey

Peter Convey

Jamie Oliver

Jamie Oliver Look out, crevasse ahead

One danger of travelling across snow and ice is not seeing what’s beneath it. A big concern in Antarctica is crevasses. These are deep cracks in glaciers and ice sheets that form when ice is under stress. This could be from glaciers flowing too fast downhill, or flowing over bumps and hollows in the rock below.

The first rule of Antarctic navigation is that it doesn’t happen if the conditions aren’t right.

If there’s a whiteout (where you can’t tell the difference between the snow or ice below and the sky above) then field teams lie up. This involves hanging around in tents, catching up on chores, drinking tea and waiting for the weather to get better.

It’s a big part of life in the field!

The best weather for spotting crevasses is when the sun is bright and low. Crevasses often have visible ‘features’ across the surface. A low sun casts shadows from these raised areas, making them much easier to spot.

Mike Brian

Mike Brian

Mike Brian

Mike Brian

A view from inside a crevasse

Crossing crevasses

If a field team reach an area where they think they are crevasses, everyone stops and slowly investigates the terrain in front of them. Someone is sent ahead to probe the ground. Very slowly, they walk forward, pushing a shovel or probe into the ground, feeling for if the snow gives way beneath them. They do this while tied on to a Field Guide or a skidoo, which will catch them if they fall into a crevasse.

If they find a crevasse, they explore further. They dig around it, finding the edge nearest to them and – if its narrow enough, the far edge. If they cross the crevasse, they’ll mark it with flags. This means if they find a crevasse ahead which can’t be crossed, they have a safe route back marked out.

Sometimes the crevasses can be crossed. Sometimes you have to go round them. If the crevasse is big enough, the Field Guide can abseil into the crevasse to see how long it is, and if they can get around it. However, sometimes the crevasses are too big and dangerous, and there’s no option but to turnaround and head back home.

Over time, Field Guides learn to read the landscape around them. They can recognise when the shape of the landscape around them means crevasses are likely, and what those crevasses might be like.

Skidoos and sledges

Meet Mike Brian – Antarctic camping expert

Mike is currently the Deputy Station Operations Manager for Rothera Research Station, but he was a Field Guide at Rothera for three seasons. We quizzed him about life on the ice.

Mike spent a lot of time travelling into the deep-field

How did you become a Field Guide at BAS?

I started out as a teacher – I taught maths and physics for ten years. I was a member of a mountain rescue team, which was a big part of how I got the job. And I’ve been a climber and hill walker all my life. For me, being a Field Guide was a job that used almost everything I’d ever learnt – teaching, mountaineering, cooking and a whole lot more.

What’s a day in the life of a field guide look like?

Digging! Definitely digging. Lifting, shifting, cooking, putting up tents, taking down tents, driving skidoos, melting snow, navigating. We also get to help out with the science too.

What’s it like camping in Antarctica?

Super comfortable, but not lightweight. Everyone has a P (Personal) Bag that goes everywhere with you, even if you’re not expecting to camp. It’s your sleeping system and it contains a foam pad, an inflatable mat, a sheepskin, a double thickness down sleeping bag, and a fleece liner and more. Super cosy – but heavy to carry!

What’s the longest you’ve camped for?

About 80 days. That’s almost 12 weeks!

How does it feel coming back?

It feels amazing! Having a shower, knowing someone else is making your tea, a fresh, comfortable bed to sleep in: it feels like the most wonderful thing in the world. Having said that, after a day or two, the outside world crowds in again. For weeks, life has been hard work and strenuous, but quite simple. But very quickly all the people you haven’t been in touch with contact you, there’s emails to deal with. It can feel a bit overwhelming and you wish you could go back out into the field again.

What’s the best bit of the job?

Being part of a small team, and working together to a common goal. I also love the challenge of making an appetising meal in challenging conditions with limited ingredients.

What about a big challenge?

Snoring scientists! It can also feel like a big responsibility, keeping everyone safe, healthy and happy – in that order. That’s especially true if you have people that haven’t been in that environment before.