Entry 1 Day 1 02 October Altitude: 9000 ft Distance: 1310 km Speed: 150 knots/hr

Up, up and away

We’ve taken off and begun our adventure to Antarctica! Our destination: Rothera Research Station, Antarctica. From there, we’ll be making the five-hour flight over to Halley VI Research Station (our famous station on skis!) and to our deep-field station Sky-Blu.

The journey began in Calgary, Canada, where our fleet of small red planes have been getting some care and maintenance. For the last few months, Antarctica has been weathering the harsh winter season, which is too dangerous for flying. But as Spring arrives in Antarctica, it’s time for a new season of science to begin.

But how do you prepare to fly a small aircraft across continents to the other side of the world? We followed the team as they got ready for take-off.

Behind the scenes of preparing to fly to Antarctica.

So where exactly are we going? We know our destination is Antarctica, but at a whopping 8,000 miles away, we’re going to need to make some stops along the way…

The ferry flights

Our planes can’t make the epic journey from Canada to Antarctica all in one go (even big commercial planes would struggle to do that) so we break the journey up into legs.

The route is planned very carefully, months in advance. The team have to check that each airport they plan to stop at is fit for our needs. They need to check that we have permission to land there, and or fly over the country’s airspace. While they land in five different countries along the way, they fly over 10 – it takes a lot of organising!

Dan Beeden

Dan Beeden

Dan Beeden

Dan Beeden Each plane is flown by a team of two, a pilot and an engineer – the dream team to keep the plane in tip top condition. They make 12 landings along the way. Some stops are called ‘tech stops’ where they land briefly to refuel and carry out any maintenance before carrying on, but most are overnight stops so the team can get some well-earned rest!

Halfway through the journey, the team will have a rest day in Panama, before continuing the journey through South America to Antarctica.

In case of emergencies – perhaps some bad weather we weren’t expecting – our Air Operations team has to make some speedy calls to get permission to land at the closest suitable airport.

Did you know?

The flight team don’t need visas to do the ferry flight, but they do get their passport stamped in every country!

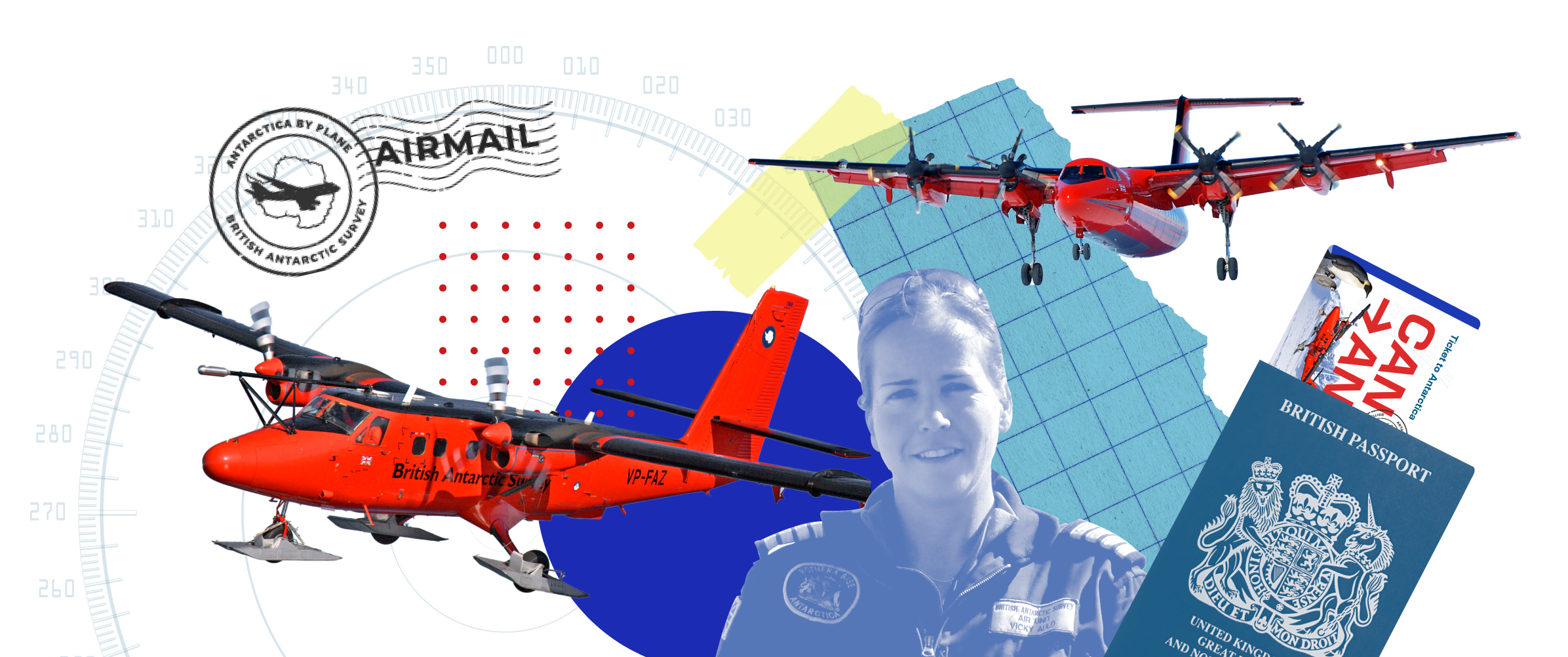

Meet Vicky Auld

Your Captain for this flight is Vicky Auld. We spoke to her to find out what life is like as a polar pilot.

What do you do as a polar pilot?

I help support Antarctic science which ultimately helps us all understand climate change better!

I fly scientists and support staff, as well as their tents, food, fuel and scientific equipment into deep-field Antarctic locations. I also fly passengers from Chile, or the Falkland Islands, into our largest research station, Rothera.

How did you end up in this job?

I actually studied atmospheric science at university, and worked at Halley Research Station as a scientist for BAS for a couple of years! As part of this, I was lucky enough to fly in the Twin Otters and eventually decided I wanted to become a pilot.

After five years of regular, regional flying, I had enough experience to start as a BAS pilot – but it took three more years to train to be a fully-fledged Antarctic pilot.

Do you enjoy doing the ‘legs’ down to the end of the world?

I love the ferry flight! I get to see the Americas from 10,000 feet, often leaving Canada in snow showers, seeing the wilderness of the Rocky Mountains, the flat plains of mid-America and the cobalt blue of the Caribbean island reefs. After crossing the Equator, we’re treated to views of jungle forests, then deserts and eventually the snowy mountains of the Andes. Of course, some ferry flights are luckier than others – sometimes we end up flying in cloud for four days!

What makes working in Antarctica different to anywhere else?

I like the autonomy, the variety and the beauty. Watching people experience Antarctic flying for the first time is often a real buzz. We get to fly through some magical landscapes that give me a serene sense of calm and joy and hold a special place in my heart.

What’s one of the best things you’ve experienced in your job?

I had a very close encounter watching two humpback whales surfacing within metres of me while I watched them from the wharf at Rothera was also a big highlight.

And what about one of the most challenging?

From a flying perspective, probably having to land at Halley Research Station in a complete white out.

Where is the best place you have flown to?

The Shackleton Mountains in Antarctica. They feel incredibly remote and are breathtakingly beautiful.

What’s one thing about being a polar pilot that would surprise people?

The amount of digging we do! We dig out science instruments, tents, fuel drums, aircraft… Not many days go by when I haven’t held a shovel!

Want to learn more about being a polar pilot?

Listen to this episode of Iceworld featuring Vicky Auld and Olly Smith, as they prepared to make the legs down to Antarctica last year.

Meet the fleet

British Antarctic Survey has a fabulous fleet of five polar planes. We’ve got four De Havilland Canada Twin otters (DHD-6) and a De Havilland Dash-7 aircraft.

Between them, they keep are polar operations running smoothly – and help us study the polar regions.

The Twin Otters

The Twin Otter is not just built for travel, but for adventure too! This awesome aircraft can carry up to four passengers, plus the pilot, and can land on snow and ice, as well as regular runways. Its job? Transporting people, food and science kit to and around Antarctica, as well as heading out on special science missions of its own.

We asked Tom Jordan – a researcher at BAS who does lots of his science on board our Twin Otter planes – for some behind-the-scenes facts about these small but mighty planes.

When it gets colder than a nippy -20 degrees Celsius, the engine oil becomes sticky and it’s hard to start the engines. So, the pilots use heaters to warm the engine up before flying and wrap the engines in special blankets to keep them warm overnight!

Science equipment used on board needs to be small enough to fit through the back doors of the aircraft. Sometimes it can take a whole week to fit all the equipment because it has to be assembled piece by piece inside the plane.

The Twin Otter can also land on rough snow and ice. The landing gear is strong but flexible, so it can bend with the bumps rather than breaking.

If pilots are landing somewhere they’ve never landed before, they will circle lower and lower, looking at the ground to see how rough it is and to check for crevasses. Then, they do something called ‘dragging skies’. They fly so low that the skis drag on the ground, but not actually landing. They then fly up and circle again to make sure no crevasses have opened. If all is good, they can then land.

Did you know?

Our most famous Twin Otter is called Ice Cold Katy?

How to land a plane in Antarctica – explained by Vicky Auld.

The Dash-7

The Dash-7 is a bit like the Twin Otter – but bigger! It has four engines and space for up to 16 passengers. It’s better for longer journeys, like flying to and from the Falkland Islands, which takes around five hours.

Ask the Air Unit

What’s it like to fly to Antarctica? What happens when you take a plane compass to the South Pole? We’re putting polar pilots and engineers in the hot seat – and you’re asking the questions! Get your thinking caps on….

Submit your questions here by 8 October and we’ll ask the team as many of your questions as possible to share in the postcard on 15 October.